My heart sank as I watched the children seated around the Kammermusiksaal covering and uncovering their mouths with a palm while making a sound. It was the first children’s concert of 2018 at the Philharmonie in Berlin. Kids often imitate what they see, whether it’s a conductor’s arm movements or, in this case, the woodwind section of our orchestra making the so-called “Indian whoop” that the composer had stuck into the Finale of his newly commissioned Alphorn Concerto. I imagined the children returning to their playgrounds, unaware of the racism embedded in their play, now legitimized by a performance in a cultural space sanctioned by adults.

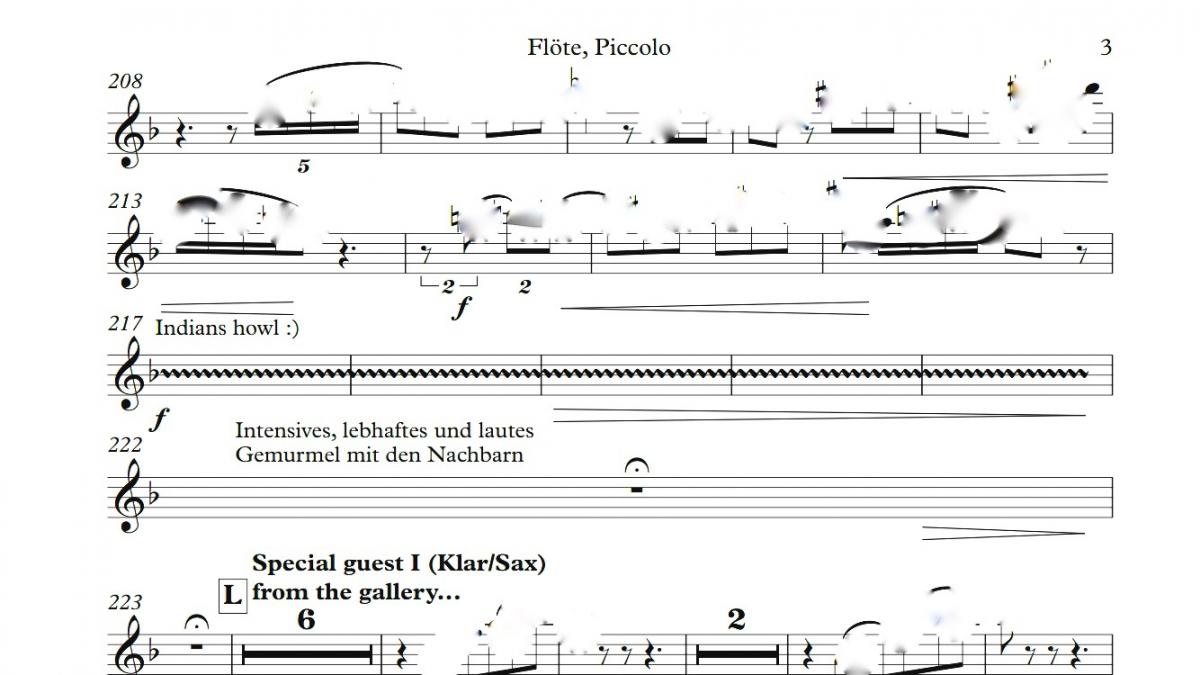

blurred because I do not have the rights to distribute the score.)

What makes this sound racist? It originated not directly from the cultural practices of any specific indigenous tribe or nation, but rather from early Hollywood depictions of Native American[1] characters. These characterizations portrayed Native Americans as a generic group of primitive, wild and violent people, ignoring the cultural diversity amongst indigenous peoples of North America and their non-European but equally legitimate forms of social organization. Native Americans existed in the white imagination as a non-civilized force that needed tamed, and this vocal gesture became associated with and a part of these dehumanizing stereotypes.

Ever since this sound effect became a metonym to represent Native Americans, it has been incorporated into racial harassment. As a recent and highly publicized example, conservative radio host Howie Carr opened a 2016 Trump rally by using the sound to mock Elizabeth Warren’s ancestry claims. Paging through Internet search results, one encounters first-person accounts on sites like Medium and the Indian Country Media Network that tell of Native American children and young adults bullied and silenced by their peers via these jeers. Coming on top of centuries of state-sponsored violence and cultural erasure, the continued use of this gesture symbolizes a wider political and social failure to address historical and contemporary forms of oppression.

To explain how this sound made its way into two concerts at Philharmonie, I will rewind to the first reading the Deutsch-Skandinavische Jugend-Philharmonie had of the piece. My peers and I had arrived in Berlin and met each other just two days earlier to begin intensive preparations for our concerts. As I was assigned an offstage part in the concerto, I watched the ensemble rehearse from the side. It was a rambunctious movement, full of intentionally silly percussion sounds like whip cracks and slide whistles. In the midst of the hilarity, I did a double take when the wind section began to whoop.

Shocked an concerned, I decided to give the composer the benefit of the doubt; perhaps people outside of the US are not so aware of the racist connotations of the gesture. Once someone points it out, surely he will change it! That evening, I emailed the orchestra manager and we set up an appointment to chat. When I described my rationale for wanting the composer to replace the sound with a different effect, she expressed support and asked whether I would like to speak with him in person or if she should approach him instead. Aware that she might have more authority and hoping to maintain anonymity, I requested that she step in.

When she returned to me the next day, the news was disappointing: he had agreed to change the name of the sound in future editions of the piece – perhaps he had misunderstood the objection. She suggested that I gather other musicians and that we approach him ourselves, in case we could explain our concerns more convincingly.

By this point, I had discussed the issue with several colleagues, and the assistant concertmaster offered to join me. Our meeting was only a few hours before the orchestra was to present a preview performance to a group of financial sponsors. The composer’s response again fell short. The members of the audience all knew him, he claimed, so they would know that he is not racist and did not mean the gesture in that way. All he wanted was a childlike expression of joy! Our attempts to reason with him, which even included suggestions of alternate sounds that might fit this description, failed, and the conversation came to an unsatisfactory close.

My colleague explained her feelings in an email after the end of the project, “If the sound had been a playing instruction in my 1st violin part I would've refused to do it... And especially - in my opinion - we as ‘role models’ should never encourage anyone to make that sound. It confuses me, that a project like this, which was obviously meant to be an amazing possibility to exchange thoughts with people from all over the world ([musicians from] over 20 nations were present) and to support intercultural understanding, it irritates me very much that there wasn’t another response to the matter.”

at the Philharmonie in Berlin in preparation for the premiere.

Backstage at the Philharmonie on the night of the premiere, the composer approached the two of us once more. He enthusiastically declared that he had a better explanation for the sound: it would be like the cries of the children in the film Ronja Räubertochter after they run off to live in the wild. To me, this reinforced the concern that he was indeed influenced by the associations of the sound with savagery, and that perhaps he thought it appropriate to juxtapose it beside alphorns, in the mountains with the cows and sheep.

Some readers might wonder, what about the composer Claude Vivier? Is his use of this sound effect in pieces like “Glaubst du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” also racist, and does that mean we should alter or bury those compositions? His case is a bit less clear and I do not have definitive opinion. While the alphorn concerto uses the sound as a joke and in a context that calls to mind stereotypical associations, Vivier uses the sound within an exploration of potential vocal timbres alongside other experimental gestures. Context and intent matter, but – then again – so do history and respect.

Though this specific incident took place in the context of a youth orchestra, it has become clear to me that there are many structural obstacles that make it difficult for classical musicians to speak up about problems in the workplace. A surplus of qualified musicians means that ensemble positions are extremely competitive, raising the stakes of being dismissed or blacklisted as a troublemaker. Decision-making power is often concentrated in the hands of very few people – in the case of the Deutsch-Skandinavische Jugend-Philharmonie, a single person is the founder, artistic director, principal conductor and composer – so a challenging interaction with that person can hit a dead end. For freelancers, ensembles are often thrown together shortly before a concert, which does not leave much time to build alliances with colleagues or to respond to an incident. Though many musicians are in unions, we often gig internationally and then do not belong to a unified supporting organization alongside our colleagues. Bad press about an ensemble or production could result in withdrawal of sponsorships, which can cause the organization to fold or downsize, eliminating a potential source of income for those musicians.

On top of all this, many classical performers and listeners alike argue that particularly instrumental music is an abstract form of art, divorced from its social and cultural context. This claim is used to silence concerns about the political implications of certain repertoire or performance practices. These concerns are cast as a distraction from what apparently truly matters – the music.

White-majority spaces need to reflect on our own racial discourses and prejudices if we wish to ally ourselves with the fight for racial justice and against white supremacy. This includes institutions dedicated to classical music. Superficial diversity or outreach efforts may look good on funding applications, but they ring hollow if they are not accompanied by reflections on how these institutions fit into broader cultural and socioeconomic power dynamics. It’s time we start having these conversations.

Sounds, Stereotypes, and Structures that Silence

x

Error message

- Deprecated function: implode(): Passing glue string after array is deprecated. Swap the parameters in drupal_get_feeds() (line 394 of /home3/rachelsu/public_html/includes/common.inc).

- Deprecated function: The each() function is deprecated. This message will be suppressed on further calls in menu_set_active_trail() (line 2404 of /home3/rachelsu/public_html/includes/menu.inc).

17 January 2018

[1] The terms Native American, American Indian, Indian and Indigenous peoples are all currently used as descriptors to encapsulate those people whose ancestors lived in North America prior to the arrival of European colonizers. Though there are compelling arguments for and against the use of each term, Native American is currently the most widely accepted, and it is thus the term used throughout this article.